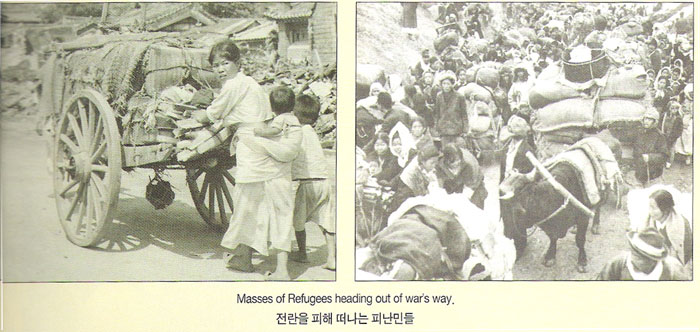

The end of the Korean War — these words send chills down my spine and a hot surge to my eyes. I was ten years old when the Armistice was signed. To me, it only meant going home from a rented thatch-roofed room in Masan, near Busan, to a tile-roofed home in Seoul. From brooks and rice paddies to a neighborhood near the East Gate lined with houses, front gates gold with brass knockers.

In 1965, I left for “meeguk,” a beautiful country, the United States of America, to do graduate work, leaving behind the American and U.N. forces to help the South Korean military to defend my country against another war. I left behind the G.I.s who had handed out Snickers bars and Wriggly’s Chewing Gum. And I left my older brother who had fought alongside General MacArthur during the 1950 Incheon Landing.

At 17, he became the equivalent of Radar in the TV series, “M*A*S*H*.” As part of the efforts to clear the way for the Landing, South Korean Navy and Marines subdued North Korean Communists on Youngheung Island. When he and the Marines captured the hill, they planted the U.N. and Korean flags, after which he returned to his U.S. Patrol Craft 703, one of the General’s 260-vessel fleet, to work his night shift.

But while he was at work, the tide went out, making it possible for the Communists to charge across the strait and annihilate the Marines my brother had fought with—among them the fourteen soldiers, to whom he had become like blood brothers.

For the next 60 years, he carried out his personal inquisition: Why was he saved? What could he do with his life to make up for the 14 lost on that island? Whenever a memorial service was held for these men, he attended it the day before, when no one was around. He could not bear to face the parents who had lost their sons. One consolation was that he had participated in the Inchon Landing.

Up until his passing away in December of 2012, he regularly visited the General’s 16-foot bronze statue standing on a pedestal in Inchon’s Freedom Park. He took a jug of “makgeolli” rice wine, poured a cup for the General and one for himself. And he talked to the General.

When a national election approached, he asked him to guide the voters so that the right person for the country would be elected. When a grandchild was expected, he shared that news with him, too. After my brother drank his wine, he took a walk around the meticulously maintained park. By the time he returned to say goodbye to General MacArthur until next time and wish him well, the General’s cup was always empty. Obviously, he enjoyed the wine.

A photo of a the statue of Gen. Douglas MacArthur and my brother, Soon-back Rhee, who at the age of 17 became a Navy communications specialist, an equivalent of Radar in the TV series M*A*S*H. 2010.

This is the U.S. PC 703 Soon-back was on as the Korean Radar.

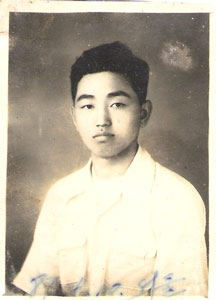

Soon-back Rhee in his Korean Navy uniform, circa 1951

Soon-back Rhee, my biological older brother who served in the Korean Navy (see above), circa 1951

-

“My Brother and General MacArthur’s Inchon Landing”

By Maija Rhee Devine

A speech given at the 8th annual appreciation picnic

held in honor of Korean War veterans

September 24, 2011, Minneapolis, MN

I knew a woman named Ceil in Laramie, Wyoming. She and I worked together in 1992 for a local museum. I did public relations. After working for a few months, Ceil and I had a lunch, and that’s when she confessed her secret. She said that she hated Koreans like me and all those who looked like Koreans—Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese—because she couldn’t tell them apart (and actually, I can’t either). She had hated Asians for 40 years because her brother was killed in combat in Korea. But she said that after working with me for several months, she began to think perhaps her brother’s life had been worth it. She saw that I was a law-abiding citizen, working hard, paying into Social Security, and most importantly, raising children and teaching them to say “The Pledge of Allegiance,” teaching them American values, those of democracy and the spirit of reaching out to those in need in this country and abroad. As you know, Americans are the most charity-giving nation in the world. She believed her brother might have saved my life and hundreds of other Koreans. So, her brother’s death might not have been for nothing. Through tears, she asked, “Will you forgive me for having hated you?” We clasped our hands and wept together. Even after twenty years, it is hard to tell this story without tearing up again.

My next story is about my biological brother, ten years older than me. I say biological because I was given away for adoption as an infant for being a girl. But he knew I was his sister, (though I didn’t know), and he visited me often. He joined the Korean Navy as a fifteen-year-old trainee and at 17, he became an active duty communications specialist, like the character Radar in the popular TV program about Korean War, M*A*S*H. Just before the September 1950 Inchon Landing, he fought in raids to clear the way for Gen. MacArthur’s American and U.N. forces. One day, he and the S. Korean Marines fought against N. Koreans on Young-heung Island in the Inchon Harbor. When they captured the peak of the hill, they planted the UN and Korean flags. After that, because he was scheduled to work on the U.S. Patrol Craft 703, he went back for the night shift. But while he was at work, the tide went out, and North Korean soldiers walked across the strait and killed all the S. Korean soldiers my brother had fought with—the fourteen soldiers he had become particularly close to were among them.

For the next 60 years, my brother lived with a survivor’s guilt. Why was he spared? What could he do with his life to make up for the 14 lost on that island? Whenever a memorial service was held for these men, he attended it the day before when no one was around because he could not bear to face the parents of those who had lost their sons. One consolation he found was the fact that he had participated in Gen. MacArthur’s historic Inchon Landing The U.S. Patrol Craft 703 was among the fleet of 260 vessels. Up until his passing away in December of 2012, he often visited the general’s 16-foot-tall bronze statue standing on a pedestal located in Inchon’s Freedom Park. He took a jug of makkoli, the Korean rice wine, and poured a cup for the general and

one for himself. And he talked to the general. When a national election approached, he asked the general to guide the minds of the voters so that the person right for the country would be elected. When a grandchild was expected, he shared the good news with the general. In short, the general had become a personal friend and a semi-god to him. After my brother drank his wine, he went for a walk around the beautifullymaintained Freedom Park. By the time he returned and said goodbye to General MacArthur and wished him well, the general’s cup was empty. Obviously, the general enjoyed the wine.